Written by Meade Palidofsky, Founder and Artistic Director

When I direct rehearsals at Warrenville every fall, I am immersed in the adolescent energy and off-stage drama around me. Overhearing a range of comments – from bursts of encouragement to sharper exchanges – I remember that often, the most challenging part of being in a show is allowing yourself to trust the whole group, to create an ensemble larger and stronger than your clique.

The risks of stepping into another person’s shoes in front of your peers, family, and strangers, can be scary. Sometimes, it’s only when the lights dim for the final time that you realize the importance of the bonds you have created on stage.

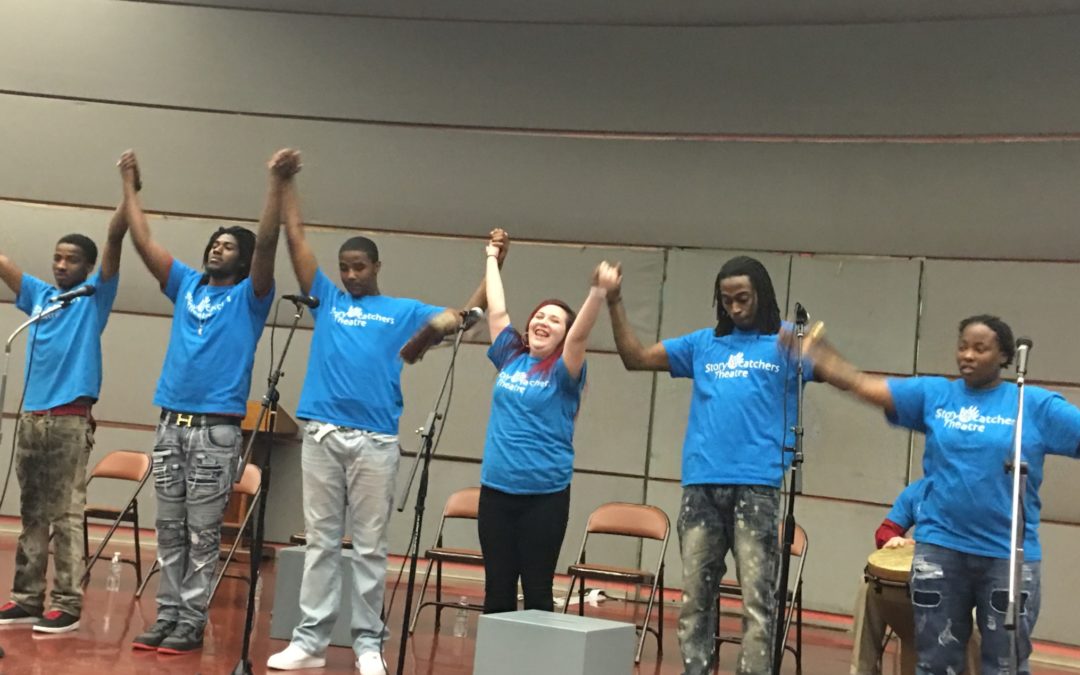

2010 Temporary Lockdown production of CHANGING MY DESTINATION

One of my favorite examples of this complicated theatrical journey is the 2010 Temporary Lockdown production of CHANGING MY DESTINATION. That play told the story of two brothers: Rolando, the 21-year-old aspiring rapper incarcerated in prison, and Corrie, 14, an up-and-coming visual artist.

During the auditions, many boys tried out for the part of Corrie, an artist who’d won an Arts Council grant to paint a mural on the wall of The Dearborn Project. As different boys read for the part, they all played Corrie as if he was his older brother’s twin: they preened and strutted, acting tough, macho, and streetwise. They missed Corrie’s sensitivity, how much he needed the world – and especially his brother – to understand that he was different, living on the edge, and, in the violent universe of the projects, often on the brink of crumbling emotionally.

The last in line to audition was Jay, a slender, ragged boy who showed a palpable streak of vulnerability. When I announced that Jay was our choice to play Corrie, there was a howl of disbelief and resentment.

The other guys thought I was out of mind to select such a loser. Jay’s t-shirt was worn and dingy, his pants hung raggedly on his skinny body. Worse, Jay wore an oversized pair of work-boots instead of designer gym-shoes. (At that time, the boys’ families could bring them shoes, and these were often the only items they possessed with any style or individuality.)

Resentful that a loser like Jay was even on stage with them, the other boys (cast as neighborhood gang members and street people) would make fun of him – of his shirt, his shoes, his hair, his smell.

By the end of the first few rehearsals, I had enough of their harassment. “You know,” I said, “if you don’t stop making fun of him, you will have no show.” They continued to mutter but stopped their overt harangues.

Jay – who had been ridiculed his entire life – began to deride himself on stage: “I’m ugly. I look bad. I smell terrible. My boots are lame. I’m worthless.”

Nonplussed, I approached him. “Stop it!” I said. He looked at the floor. “Focus on your character. Corrie is an artist. He wants to create something beautiful in a dirty, disintegrating world. There are prison-like bars on the project’s windows. Corrie’s charge is to transform this universe. When you’re here in rehearsal, don’t focus on yourself. Focus on being Corrie.”

With that permission, Jay began to inhabit Corrie’s inner world. Every day, he added some nuance to the part of the younger brother, covering a world of pain with paint. As the rehearsal process progressed, the boys who had tortured Jay began – reluctantly at first – to see his merits: the ways in which he surprised us with a line-reading, his focus, and his intense desire to live out all of his emotions on stage.

One day, Melvin, whose mother had brought him a new pair of shoes, quietly brought Jay a pair of gym shoes. The work boots disappeared.

We had five performances of CHANGING MY DESTINATION. The final show was for family and community members. Every boy had someone attending except for Jay, whose mother was in drug rehabilitation and whose father was in prison.

That night, Jay gave an exceptional performance. In the play, Corrie meets a young girl new to the Dearborn Project. Jealous of Corrie’s art, she plots its destruction, and the night before the mural is unveiled, the girl succeeds in destroying it. Corrie, on the brink of despair, looks up to see the community, including gang members, coming together to restore his work.

When the play ended, and the applause of the audience faded, Jay realized that his moment of triumph was over. As the other boys gathered with their families at the post-show reception to eat, Jay stood alone on stage. He began to cry and then sob as it hit him: it was over. No more rehearsals. No more performances.

As Jay’s body shook, all the boys who had once tortured him left their families. They encircled him. They held him in their arms. They invited Jay to join them and their families. They had realized how his extraordinary commitment to the play had bolstered theirs, that his experience had made theirs better. That he was not ugly, not a loser. Inside, he held the light that made them all shine.